In a recent LinkedIn post, Miryam Seers, a lawyer-linguist and Chair of the ICC Canada Arbitration Committee, highlighted a rather egregious instance of mistranslation caused by the use of unrevised automatic translation by the French Ministry of Justice.

The original text is entitled “Sauvegarde de justice d’un majeur” – that is, a temporary measure to protect an adult on the grounds of their disability.

As stated on the French Ministry of Justice website, sauvegarde de justice is a legal protection measure by which the individual retains the ability to perform all acts save for certain important acts, such as selling real estate or taking out a loan for a significant amount, which may be entrusted to a representative.

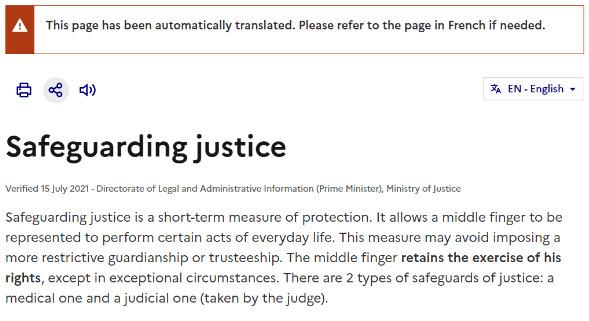

Below is the original post on the Ministry’s website:

In the first paragraph, “majeur” (an adult) is translated as “middle finger”. Given the rude connotations of this digit, the sentence The middle finger retains the exercise of his rights becomes unwittingly, and rather embarrassingly, hilarious.

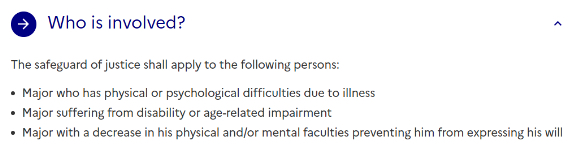

In the bullet points following that paragraph, “majeur” is rendered as “major” – less awkward, but still well off the mark.

Furthermore, the possessive pronoun is systematically translated as “his”, which is not well suited to current convention, particularly for a government institution whose communications are expected to set the standards for inclusiveness.

Though the issue was apparently detected one month ago, the Ministry is yet to take action. Not for lack of warning – indeed, the French Society of Translators (SFT) has released an official statement regarding its position on the use of AI in translation and interpretation (the English version can be found here). It warns, among others, of these risks:

- Loss of quality.

- Loss of confidentiality.

- Legal, economic, liability, security, reputational, manipulation, and error risks.

- Breach of copyright.

- Professional precariousness.

- Environmental damage (through the consumption of resources required to power AI).

- Misinformation, falsification, and data manipulation.

The SFT’s statement also highlights the benefits of working with a linguistic expert: translators and interpreters craft bespoke content, with a critical eye on the source material to spot errors and incoherencies; they provide a contextual analysis that enables them to adapt the message, its tone and style; and they bring their personal responsibility, ethics and sensitivity. All elements that machines are unable to provide.

What lesson can be drawn from this mishap? That AI is a tool and one to be used with care at that – certainly never unsupervised by human beings.

As an aside, we have witnessed the effects of non-consensual (mis-)translation in our own website.

When faced with a translation – particularly in such a delicate context as legal translation – quality, accuracy, and responsibility are paramount. As Seers points out, sometimes not translating altogether would be preferable to mistranslation. In her words:

Il faut tout donner ou laisser tomber.

”Either give it your all or leave it alone.”

In this article:

“Non-consensual Translation” (2024) https://boethiustranslations.com/non-consensual-translation/

“Sauvegarde de justice d’un majeur” (2023) https://www.service-public.fr/particuliers/vosdroits/F2075

Seers, M. (2024). https://www.linkedin.com/feed/update/urn:li:activity:7218955062004305920/

Statement on artificial intelligence by the Steering Committee of the Société française des traducteurs (2024) https://www.sft.fr/global/gene/link.php?doc_id=551&fg=1

“Tutelle, curatelle, sauvegarde de justice : quelles différences ?” (2023) https://www.justice.fr/fiche/tutelle-curatelle-sauvegarde-justice-differences